How To Build a Nation from Rubble

It never occurred to me that there was a real possibility of getting shot here. I was on assignment to write a story on what has happened since East Timor gained its independence from Indonesia just one year ago. Nationhood had proven to be a difficult birth. There had been a brutal 23-year struggle between the Timorese freedom fighters (known as the Falintil) and the Indonesian regular army. Finally, on May 20, 2002, East Timor emerged as the world’s newest country in the family of Pacific island nations.

From the very first day of my arrival at Comoro Airport in the capital city of Dili, I felt a little edgy. I saw heavily armed soldiers from the UN multinational peacekeeping force amble along an otherwise peaceful looking section of beachside near my room. Years of living in my home state of Hawai‘i had taught me to enjoy the serenity of waves lapping tenderly onto the shoreline. In East Timor, a false sense of tranquility could prove to be an illusion that might get you killed.

The East Timorese have not been free for over 500 years. Back in the 16th century, Portugal and the Netherlands divided a tiny, cigar-shaped volcanic islet and made the people to the west a part of the Dutch East Indies (now known as Indonesia). The eastern portion of the island became the Portuguese colony known as Timor Leste and remained a colonial outpost until November 18, 1975. But a mere nine days after decolonization by Portugal, Indonesia invaded East Timor.

Against all odds, the East Timorese people organized a guerilla force and began a struggle for freedom that would last almost a quarter of a century and result in the death of every third person on the island (an estimated 250,000 lives). When the Indonesian forces were told to withdraw in November 1999, they were also told to burn everything in their path. They burned to the ground every village and town and hamlet and city. The domesticated animals; cattle, pigs, chickens, dogs, and goats were shot on sight as they ran from the fires. Civilians silhouetted against the ubiquitous conflagration were also shot. Thousands died in the last two weeks of the occupation alone.

The communications infrastructure was wrecked. The water treatment and sewage facilities were destroyed. The electrical plant went off-line – permanently. As a final insult, the tiny island roughly the size of Connecticut and not more than a dot in the Great South Pacific Sea, literally went black. And still the people of East Timor lived to celebrate their victory and new-found freedom just last year.

East Timor’s first democratically elected President, Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão, has set up shop in a building located centrally in the Caicoli District. It is not much, as Presidential Palaces go. The banner over the doorway reads “Palacio das Cinzas.” To the left of the grand entranceway, a couple of goats, pigs, and a milk cow wander around in an adjoining lot. Large portions of the shiny, white tile façade that once adorned the building are gone. Black and grey patches scar walls where flames once leapt up through windows and doorways. And the roof is missing.

In any other country this place would have been cast aside like the trash that dots the roadways. But in East Timor, this is not simply another burned-out building like the hundreds of others that line the streets. This carcass of a structure, as modest as it is, is the seat of government for the new country and has been consecrated by the President as his “Palace of the Ashes.”

“I am afraid when you meet the woman here, many are widows. The war was bad time.” This warning came from Olandina Alves, a kind, 50-ish, Timorese woman who sat across the aisle from me in our little plane as it banked to land. We had spoken briefly in Denpasar, Bali as we sat in the waiting room. She introduced me to Mize, a young girl traveling with her. Mize had been put in jail with her biological mother at age four and was there with her for nine years. Sometime later Olandina became her mother. All Olandina told me was that tens of thousands of the local maubere (native Timorese) went into the Indonesian prisons during the war and never came out. Today, nearly half the population is less than 20 years old.

I was scheduled to meet with President Gusmão on Saturday morning, June 21, 2003. His birthday was the day before and I had accidentally stumbled onto the party organized for him by his office. Everyone was neatly dressed in spite of the dreadfully humid and torrid heat. I was the only person there with foreign press credentials and quite obviously an out-of-towner. I wiped my forehead with the sleeve of my shirt as I approached him. While looking directly into my eyes, he cradled my hand and said in a gentle voice, “I am so happy to meet you.” I had never met the leader of any country before let alone someone regarded by his people as a saint. All I recall doing in response was sweat.

He immediately joked, “he had only one more year left to live.” I gave him a quizzical look. He explained that according to government statistics, Timorese men have a life expectancy of only 58 years. But his eyes still had the intensity of a bird of prey. And he had large hands. President Gusmão told me they were well-suited for the pumpkin farmer he dreams of becoming when his country is finished demanding five years of his life in political service.

He had been a busy man over the preceding ten days. He had met with Secretary General Kofi Anan of the United Nations, President Jacques Chirac of France and President Jorge Sampaio of Portugal, all of whom were bestowing awards upon him for his courage and sacrifice.

He once studied, at the insistence of his impoverished father, to become a priest. It didn’t take. He worked as a civil servant for the Portuguese colonial government and left with a smoldering resentment for colonial exploitation. He became a journalist long enough to witness the Portuguese government decolonize his country. He wrote poetry and received some critical acclaim. But when Indonesia invaded East Timor, he put aside his intellectual life and became a fiery revolutionary.

The future President and commander of the resistance lived in the jungle for 17 years and eluded capture, survived dengue fever and the killing effects of malaria. But in 1993, on an informant’s tip, he was arrested in Dili by the Indonesian authorities. Xanana Gusmão was taken to Cipitang prison in Jakarta and held for trial on the charge of treason. His conviction and sentence to life imprisonment was widely known to have been preordained.

But his captors could not have foreseen that Xanana Gusmão would turn his Jakarta prison cell into his platform to the world stage. He taught himself English and began to write to the leaders of the free world. He became known the “Mandela of the Pacific.” President Clinton and other western political leaders began to exert pressure on the Indonesia government. Much to the displeasure of the Jakarta authorities, Indonesia’s dirty little war was about to come to an end.

Leading has not been easy, even for a man viewed by many of his countrymen as a saint. Take for example, the problem associated with inheriting an extravagantly bloated bureaucracy. Under Jakarta’s rule, government jobs were traded for support. Pay checks bought allegiance. But the now virtually broke but free country was in danger of sinking under its own administrative weight. These civil servants were dubbed ignominiously as Battalion 702 and came to symbolize the gross excesses in government inefficiency: they arrived at work at “7”, did “0” work all day and departed for home at “2.” When thousands of them were dismissed as part of a restructuring effort, the resentment poured out of the buildings and filled the streets of Dili with an angry and, now unemployed mob. Although many dispute whether this was the seed of the militant discontent leading to the riots of December 4, 2002, if it did not play a direct role in causing the uprising in the streets, it certainly did not help.

But there is also optimism in the streets of Dili and in the countryside. I asked Zoni Ximus about being free of Indonesian rule and in broken English he told me that “Freedom good!” but then complained that “Life hard.” Estaves Barrito, who drove me to the Presidential home in Balibar, saw his freedom as something even more concrete; “Now I go home (to Bobonaro) when I want. No more Indonesia police. No more papers to show.” He popped a cassette into the tape player and began singing along to the lyrics “Livin’ that honky-tonk dream!”

Commerce, however grudgingly, is returning to Dili. Vegetable stalls and prepackaged goods like soap, candy and cookies are being sold at a bustling open market at Tabesi. There are two public pay phones in Dili (that I know of) operated by Timor Telecom. Three young Chinese entrepreneurs have opened “Alink Computer Café,” the city’s first internet business to open in spite of the unreliable electrical service and even more unreliable telecommunications uplinks. And along the Avenido Bispo Medeiros you can get a Thai massage. Unfortunately, most of these services are affordable only to foreigners working in association with NGOs or UN support personnel since the average daily wage for a Timorese is about $3 USD a day.

Money is finally beginning to flow into the government’s coffers and that will certainly help jump start the fledgling economy. In June of 2003, the Government of the Northern Territory of Australia, in partnership with American oil behemoth Conoco Phillips, endorsed a contract to develop the Bayu Udan natural gas and oil reserves in the Timor Gap. The revenues to the young nation over the next 17 years are projected at 6 Billion USD. And this is the small field. The apple of the eye of the petroleum and natural gas producers is set on what is known widely as the “Sunrise Field.” Estimates project that sales and revenues from this project alone could be 10 times that of Bayu Udan. Although the Australian government will deny it, some suspect that their willingness “to look the other way” during the invasion and occupation of East Timor was the quid pro quo for continued access to Indonesian oil and markets.

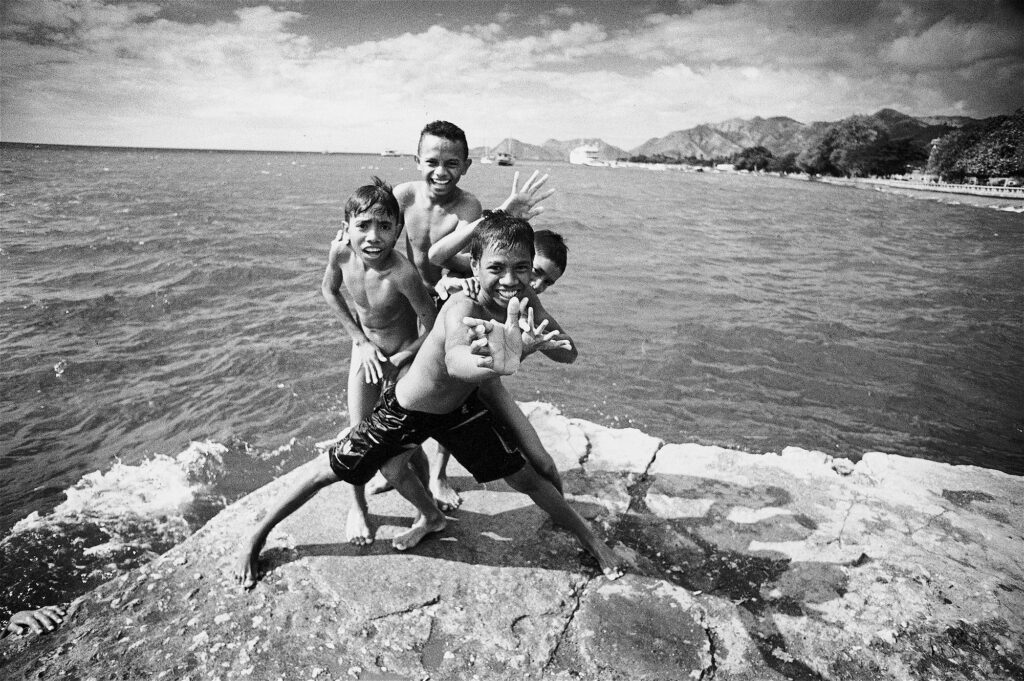

“We have many problems,” the President told me in a level of honesty uncharacteristic of politicians. “We are such a poor, poor, country.” In fact, East Timor is ranked in the 10 poorest countries in the world and nearly dead last in per capita GDP. But wealth is a relative concept. The maubere refer to East Timor in their native tongue as Timor Loro ‘Sae, which means “Island of the Rising Sun.” It has lush tropical shorelines rich with fruit. It has glassy clean waters abundant with reef fish. It has a mountainous region which supports a coffee bean industry appreciated by connoisseurs. It is a beautiful island especially now that the East Timorese people have the chance to enjoy their home in peace.